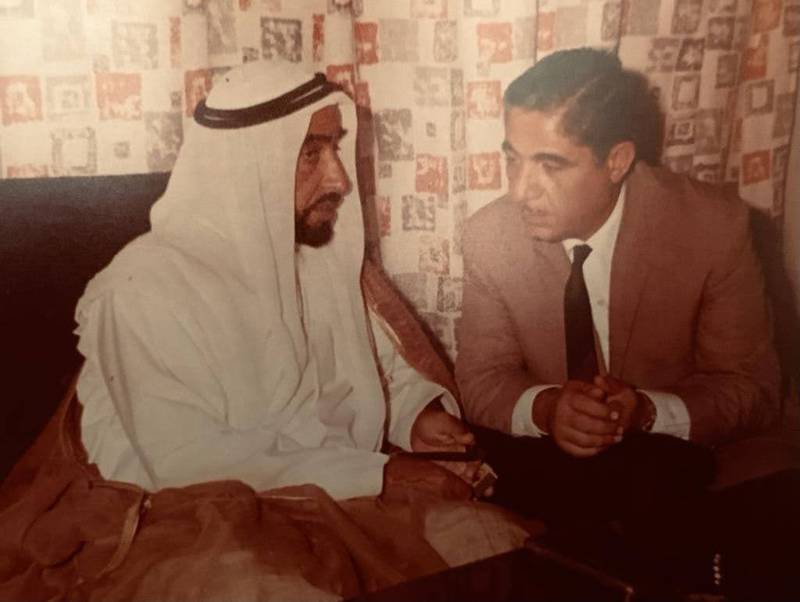

Moussa Abadi and his French wife Odette hid hundreds of children from the Nazis in homes, convents and orphanages across southern France.

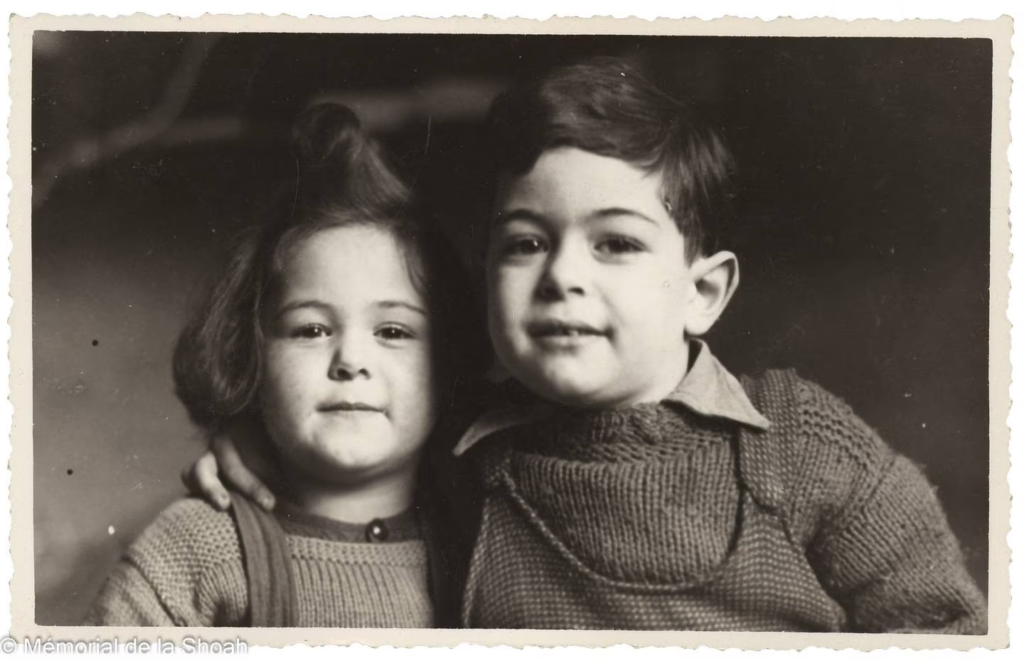

Andree Poch-Karsenti was not even three years old when her parents were rounded up at their home in the southern French city of Nice, on a quiet street above the Mediterranean Sea.

She escaped the clutches of the Gestapo, playing obliviously with her neighbour Jacques on the other side of the street.

Her parents and aunts would not survive the war, after being sent to concentration camps in Drancy and then Auschwitz.

But thanks to a clandestine network set up by a brave Jewish couple — a French doctor and a Syrian man from Damascus — Andree avoided the Gestapo.

Moussa Abadi was born to a religious family in the Jewish Quarter of Damascus in 1910. He attended a school run by French priests, which would fuel his eventual move to Paris in the 1920s.

When the Nazis invaded Paris in 1940, Moussa fled south, leaving the capital on a bike with one change of clothes.

He arrived in Nice, later to be occupied by the Italians, where thousands of Jewish families sought refuge. Damascus urged him to return home but he refused.

One day, under a “postcard-blue sky”, Moussa saw a young Jewish woman being beaten to death by a French policeman on the seafront promenade.

While the Nazis ruled the north, the Italians kept the Jewish population relatively safe ― for a time.

But Moussa knew the Germans could push south. Even under the French authorities, round-ups in early 1942 sent thousands of Jewish families to their deaths.

Moussa later met an Italian priest who told him of Jewish children being massacred by the Nazis.

These two encounters pushed him to take the biggest risk of his life, alongside the woman who would later become his wife, Odette Rosenstock.

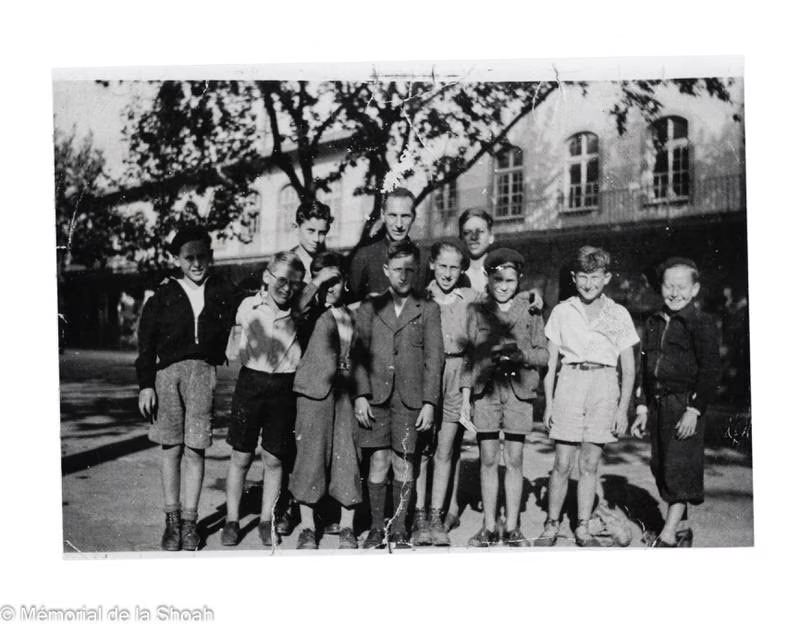

Andree was one of the hundreds of children who were hidden by Moussa and Odette as part of the Marcel Network, established by the couple in 1943 after the German invasion of Nice.

Within a year, they saved 527 Jewish children with the aid of local families, Christian clergy and children’s homes. Many of them would be later honoured by Israel as one of the “Righteous Among the Nations” for their bravery.

Andree is now 82, and lives near Paris. But for decades, she knew nothing of the couple who helped her escape the Nazis.

“I knew that I was hidden with the Rous [family] and that my parents were deported, but I didn’t know the rest of the story. No one had spoken to me about it,” she tells The National.

Andree was taken in by her neighbours, the Rous, and hidden in a mountain village until the spring of 1944, when the Gestapo arrived to take on resistance members.

She was then taken back to Nice and put in a children’s home by Odette and Moussa.

It wasn’t until 1995 that fate would bring them together, when her brother came across a list of children hidden during the war.

Odette was looking for them. Andree called Odette and found the couple living not far from her home in Vincennes.

“They were an extraordinary couple, who led an extraordinary life,” she says.

“They could have gone into hiding but they decided to risk their lives to save children condemned to death. They are courage personified.”

The couple would meet with some of the hidden children later in life, gathering at restaurants in Paris and meeting their grandchildren.

On rare occasions, they would invite them to their modest apartment in the 12th arrondissement.

Odette, a French doctor from Paris, had met Moussa in 1939. After fleeing to Nice, she began working at a clinic for Jewish children on the Boulevard Dubouchage, where she would tell families: “If the Germans come, we can hide your children.”

They had no money and no connections. Both Jewish, they were at risk of deportation and death.

“Every morning when I drank my coffee with Odette, I didn’t know whether I would find her safe that evening, or even whether I would be alive,” Moussa later wrote.

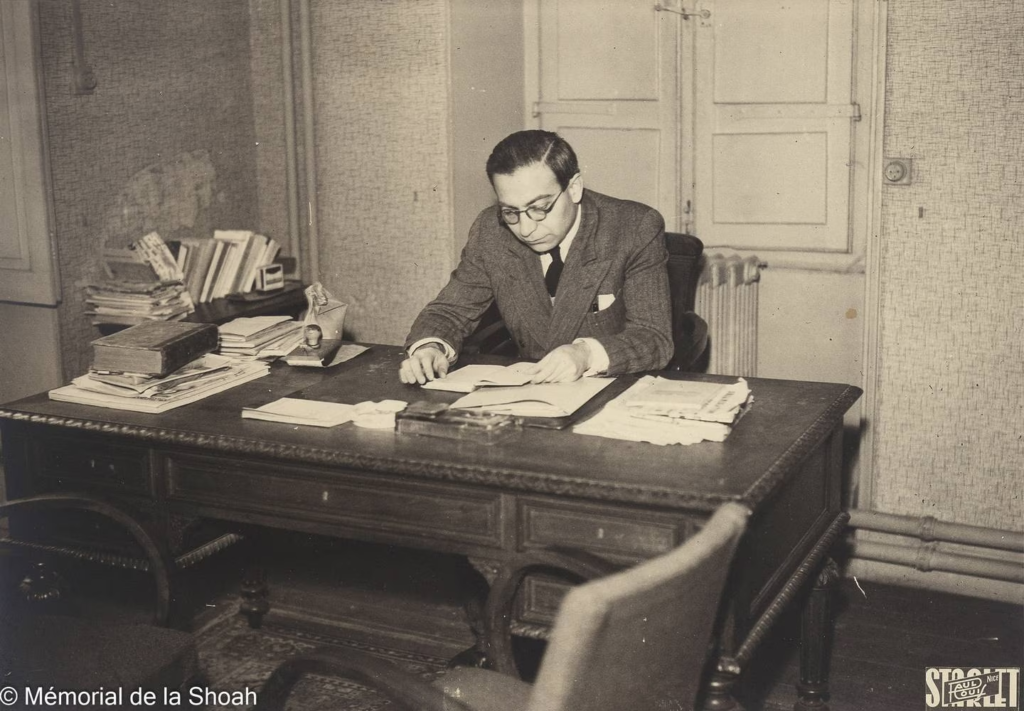

He met the Bishop of Nice, Paul Remond, imploring him to help save children from the Nazis.

The bishop gave Moussa an office in his home, on the ground floor so he could escape if and when the Germans came.

It was here that Moussa made thousands of fake documents, baptism certificates and ration cards. In the garden, he buried files that would help reunite the children with their families at the end of the war.

Odette enlisted the help of local children’s homes and Protestant priests near the synagogue on Rue Dubouchage, who appealed to local families for help.

Children were taken to a “depersonalisation” house where they learnt their new identities, drummed into them before they were sent into hiding.

Some of them were so small they couldn’t speak French or understand why their names had changed.

Some children hidden together would take turns sleeping, terrified they would reveal their real identities as they slept.

“We had to teach them 10 times,” Odette recalled in an interview.

“They carried secrets that were too heavy for children,” Moussa said.

Daniel Czerwona-Jagoda was one child hidden by the network, placed in a convent at the age of five.

When the war ended, his father searched Nice for weeks by bike, looking for his son at each convent in the city.

He finally found his son thanks to a Polish nun.

“Yes, Daniel is here, but his name is now Daniel Blanchi,” she told him.

Now 84, Daniel wrote poetry later in life and signed it with three surnames — Czerwona-Jagoda, Blanchi and Chervonaz. The last he chose as an adult, fearing another war may break out.

“Odette and Moussa, I was really touched by what they did,” his daughter Sarah told The National.

She paid tribute to the couple and her father in a show inspired by his life and childhood memories, where “small children had to act like grown-ups. Little, by little, they had to change who they were because their lives were on the line”.

Despite his experience, her father has taught her to be positive, that you must always move forward, but his experience has stayed with him.

“There were little flashes,” Sarah says. “If we had to be quiet, we had to be completely quiet and still. It was as if it could endanger the whole family, that there might be a knock at the door.

“But there was always a reason, never a complaint. It was never negative.”

‘You owe us nothing’

The Catholic church gave Odette and Moussa false titles to allow them to escape arrest and visit children hidden across the diocese.

Odette would call on the children, posing as a social worker, while Moussa remained at the bishop’s office making documents.

Only two children hidden by the network were arrested, after their hiding place was betrayed.

Odette saw them on a bus, and was shooed away by one of the children when she realised they were surrounded by plain-clothes police.

She was arrested two days later and deported to Auschwitz.

As a doctor, she worked at the camp clinic and was privy to many horrors out of reach of other inmates, trying to save sick prisoners from being chosen by Josef Mengele, who was known as the “Angel of Death” for his experiments on prisoners.

Odette was later sent to Bergen-Belsen until the liberation.

Moussa was left in Nice to run the network alone, also evading capture by the Nazis. He started going to Catholic Mass at a different church every few hours to try to stay under the radar.

After the war, Odette would confess she fared better than Moussa, saying it was sometimes harder for those who were not deported.

Moussa and Odette told almost no one of their heroic efforts that earned them several of France’s highest honours.

Moussa went on to become a renowned theatre radio critic and wrote two books on Jewish life in a Damascene ghetto, while Odette rose up the ranks in medicine and later worked at a school for deaf children.

They refused to speak publicly until they were in their 80s, when the stirrings of Holocaust denial began in France.

“When we meet hidden children again, the question they ask most often is, ‘How can we thank you?’” Moussa told the French Senate in 1995.

“My response will be brief. You have nothing to thank us for, because you owe us nothing. It is we who are in your debt.”

Moussa kept in contact with his family from Syria, visiting his cousin in Argentina where he confided in some family members of his wartime past but swore them to secrecy.

“I felt as impressed in the way one would if they spoke to Clark Kent. He was a superhero, a real superhero,” his cousin’s grandson Carlos told The National.

“They only spoke about it because they felt they had to. He wanted to take it with him to his grave.”

Moussa’s health declined in the last years of his life, until he was almost blind. He died of stomach cancer in 1997.

Odette spent the last two years of her life collecting all of the documents, finishing the transcription of a book he dictated to her as his eyesight failed.

She died by suicide in 1999, writing that she had died along with Moussa.

“They were a couple of the kind we don’t see today,“ says Andree. “They loved each other. She did everything she could so his memory would endure. She always put him first.”

Andree now runs the “Friends and Children of Abadi” association, which serves to tell the story of the Marcel Network.

“Because Odette and Moussa had never said anything, no one knew about them. We want to continue their memory and that of the Holocaust. As long as I’m able, this is what I will do.”

source/content: thenationalnews.com (headline edited)

___________

_________

SYRIA