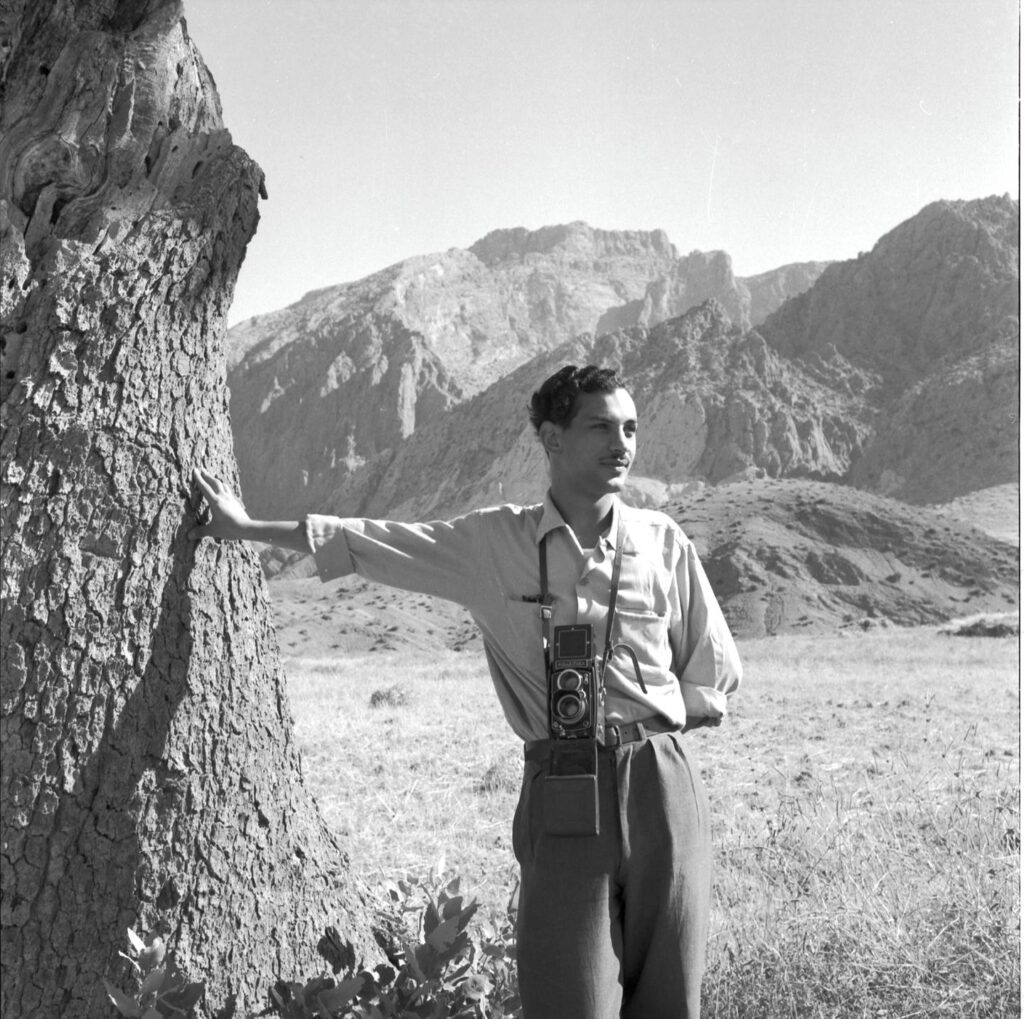

The New Arab sat down with Yemeni documentary photographer and storyteller Thana Faroq to discuss intentional photography, craft, and nurturing intimate narratives of displacement and resilience.

Thana Faroq is a Yemeni photographer and educator based in the Netherlands. Her photography projects, which have been supported by the Arab Documentary Fund and the Magnum Foundation among others, blend text, physicality, emotional density, and visual storytelling, to explore immigrant lives and the complexities of belonging and trauma.

The New Arab interviewed Thana Faroq on the occasion of her new book, How Shall We Greet the Sun, which follows a group of displaced young women including Faroq herself, as they negotiate their multilayered presence in the Netherlands.

“My work is mainly driven by current events and broader themes, such as intergenerational trauma and memory resilience in relation to migration and refugees”

The New Arab: You’ve completed several series and projects, including your new photo book, How Shall We Greet The Sun. How do your various projects communicate with one another?

Thana Faroq: At the core of all my work, including How Shall We Greet The Sun, lies an exploration of women’s resilience, adaptability, and the quest for belonging. These themes are the threads weaving my projects together, creating a continuous dialogue.

A consistent focus in my projects has been on the aftermath of pivotal events, particularly in migration. I’m drawn to understanding and portraying the lingering effects, the changes, and the adaptations that individuals and communities undergo in their post-disaster homes.

My projects often converse with each other, providing different facets of a broader narrative about migration, displacement, and the aftermath of these transformative events.

It is essential to explore these events not only in terms of their immediate impact but also in the ripples they create over time. How does our survival, resilience, loss, and search for identity and belonging look like? While my earlier works might have explored the immediacy of events, more recent ones, like How Shall We Greet The Sun, dive deeper into the lasting, often nuanced, emotions and memories that remain.

Do you feel that your work has evolved in terms of craft, technique, and vision? I saw that you have incorporated more poetry and written text recently.

Certainly. I spent my formative years in Yemen and from the age of seventeen, my educational journey took me across the globe, in Canada, the US, and the UK, which significantly broadened my perspectives.

It’s also crucial to acknowledge the life-altering events I’ve encountered: the war in Yemen, the subsequent move from my homeland, and the pursuit of asylum in the Netherlands. These profound experiences have shaped my life and continue to influence my understanding of the world.

This, in turn, has expanded my artistic vision. I’ve become more intentional about the themes I choose to explore and the stories I wish to tell.

Over the years, I’ve continually sought to refine my craft, exploring new techniques, tools, and mediums, especially sound and moving images. I love writing and it has become part of my creative journey and output.

I can’t label my written explorations as ‘poetry’ in the traditional sense, but I do have a deep affinity for playing with words, treating them as visual elements in their own right. I don’t view them merely as ‘texts’ but as visual companions to my images.

When paired with my visuals, these words offer an additional narrative layer, adding complexity and depth to the story I’m telling.

How do you approach storytelling in your work? Stories have a beginning, a middle, and an end, but using real-life subjects means that this linear, theoretical approach might prove restrictive.

I agree with you and I don’t personally stick to the classical structure of storytelling. All my stories are rooted in real-life experiences which means I will have to challenge this conventional approach of storytelling.

I ask myself very often: does a linear progression truly capture the essence of this experience, or is a non-linear narrative more authentic? And so my starting point might differ, I might start in the middle of a story with an emotional state that sets the tone for the narrative. My approach focuses on deep research and understanding. I immerse myself in the subject matter.

This helps me understand the nuances, the emotions, and the various perspectives that exist. Though all my projects exist in a final outlet (for example, a book) the creative process is never linear. I have a lot of responsibility to stay true to the essence of my subject’s experiences and sometimes this means breaking away from traditional structures or inventing new ones.

Also, storytelling isn’t just about the narrative; it extends beyond the mere sequence of events or plot points that make up a story. It’s about conveying experiences, emotions, and messages. For me, it’s about the use of texts, imagery, and symbolism to evoke feelings and provoke thought.

Though photography is my main medium, I include sensory elements, such as sounds and texts which can elevate the story and make it more immersive, especially in installation settings. This multilayer experience is powerful. I’m deeply intentional in my approach.

Before capturing or selecting an image, I reflect on its purpose: ‘What story am I conveying? How does this differentiate from the masses? What emotions or messages am I trying to evoke? This reflection ensures that my work carries depth and isn’t merely a fleeting visual in an endless scroll.

Are you looking for that person’s specific story in your photos or rather how they symbolise something bigger, larger than their own selves?

My work is mainly driven by current events and broader themes, such as intergenerationl trauma and memory resilience in relation to migration and refugees.

Every individual is a microcosm of the larger society they inhabit, and their stories, while personal, often resonate with universal themes. I work to make my images evoke shared experiences or emotions for a wider audience and, to a certain extent, the individual here becomes a symbol of something larger while ensuring that the individual’s story doesn’t get lost in symbolism.

Narratives that illustrate their character, resilience, culture, family ties, and personal history can help dismantle stereotypes and build a deeper understanding. This also means providing contextual cues within the composition. I write a lot during the process and these texts allow the viewers to draw connections between the personal and the universal.

“Photography, as I see it, is a shared endeavour from the research phase to execution. I prefer to refer to those I photograph as ‘collaborators’ involved every step of the way, valuing their insights and feedback. This often paves the way for deeper intimacy”

How do you nurture trust and intimacy with your subjects? Is there a story you chose not to tell?

My personal background plays a crucial role. As a woman refugee myself who has experienced the impacts of war and trauma first-hand, I share a common ground.

When I interact with my subjects, I approach them not just as a photographer, but as someone who has walked a mile in similar shoes. I don’t shy away from sharing my personal journey when appropriate, as I find that this openness can lead to mutual trust and safety.

Photography, as I see it, is a shared endeavour from the research phase to execution. I prefer to refer to those I photograph as ‘collaborators’ involved every step of the way, valuing their insights and feedback.

This often paves the way for deeper intimacy. Open communication and transparency are also pivotal. I make it a priority to be clear about how the photographs will be utilised, whether as an exhibition, a book, or any other medium, which helps bolster trust and comfort.

I approach each shoot with sensitivity, recognising and respecting the emotions and vulnerabilities of my collaborators. This journey of empathy, trust, and intimacy is complex and requires time, honesty, and sincerity.

There have been instances where I’ve chosen not to share certain stories out of respect for the privacy of those photographed.

For instance, in my recent book How Shall We Greet the Sun, there are many emotional transitions that migrant women undergo as they settle in a new place. Discussing these transitions isn’t always easy. I only choose to reveal such narratives when my collaborators are ready and confident to share them with the world.

For the young generation of aspiring artists in Yemen and elsewhere, could you share what helped launch your career and any advice you may have for others who can’t rely on institutional support and backing?

In my journey as an artist and photographer, I’ve come to understand a few key truths that I believe have been instrumental in shaping my career, especially in places like Yemen where institutional support might be sparse.

While talent is a gift, discipline and hard work are choices. Talent might get you started, but discipline will carry you through. It’s crucial to stay true to your artistic vision.

Instead of creating what you think others might want to see, focus on what you passionately believe needs to exist in the world. Also, the art world and photography, like any other field, constantly evolve.

Stay open-minded and eager to learn from others, peers, mentors, friends, and family… every interaction can offer a fresh perspective that can enrich your work.

Farah Abdessamad is a New York City-based essayist/critic, from France and Tunisia / Follow her on Twitter: @farashstlouis

source/content: newarab.com (headline edited)

_____________

__________________________

NETHERLANDS / YEMEN