The University of Rhode Island neurotoxicologist and dean came to the U.S. for college in the 1980s.

Nasser Zawia hails from Al Bayda, a town in the south of Yemen, a country that has long been affected by war and is currently experiencing widespread famine. Zawia traveled to the U.S. in the 1980s to earn an undergraduate degree from the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He stayed in America, obtaining a PhD in pharmacology and toxicology from the University of California, Irvine. But Zawia never planned to stay on in the U.S. permanently. “Like many students who came here in the 80s, the objective was to come to go to school and go back to your home country and serve there,” he told The Scientist. “However, I married an American citizen.”

In 1990, Zawia and his wife moved to Yemen, where he planned to take a job at Sana’a University’s medical school. But the first Gulf War broke out in 1991. “The war was between Kuwait and Iraq,” he said. “But at that time, the position of the Yemeni government was supportive of Iraq. The connections with the U.S. were being threatened. I left during a climate where there was a lot of uncertainty and fear and insecurity as to what might happen.”

Returning to the U.S. in 1991, Zawia used connections he had made in US universities to secure postdoctoral positions at the University of South Florida and then at the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina. After studying environmental toxicology at NIEHS, Zawia landed a faculty position at Meharry Medical College, a historically black college in Nashville, Tennessee, where he studied the developmental effects of lead exposure in minority populations. “I found that to be something where I could serve the underserved,” he said. “I stayed there for five years and then moved to the University of Rhode Island.”

Although he was successfully navigating the halls of academia and earning his citizenship in the early ’90s, life in the U.S. was not easy for Zawia. “The U.S. was not very receptive to people from the Middle East at that time because of the first Gulf War,” he recalled. “Those of us from that region of the world, our life is always punctuated by all kinds of events involving war. Every 10 years it seems like something big happens, which impacts us in many ways.”

The next big event that would have an effect on Zawia and countless other Americans happened on September 11, 2001. “Those of us who are Arab Americans/Muslim Americans in this country have always been dealing with wars and difficulties in our ancestral homes. But we didn’t ever think or expect that someone would come to the U.S. and cause such a catastrophe. And it changed our lives a lot. And everybody else’s,” he said. “But still we were Muslims in the U.S., and we had to deal with the Patriot Act and then the NSEERS [National Security Entry-Exit Registration System] registration for citizens coming from Muslim countries.”

Despite anti-Muslim sentiment spawned by the terrorist attacks of 9/11, Zawia chose to stay. Since setting up his University of Rhode Island (URI) lab in 2000, he’s made seminal discoveries, including research that pointed to a developmental basis for Alzheimer’s disease. He and his colleagues found that early exposure to lead increased the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease–related pathologies later in life. Zawia is now working on the epigenetics involved in this phenomenon, and said that his team is pursuing clinical trials of a repurposed drug to treat rare types of neurodegenerative disorders in Europe.

Although the Trump administration’s executive orders on immigration have restricted some travel for people from several countries in the Middle East, including Yemen, the policy has not directly affected Zawia, a naturalized US citizen. But both as a scientist who attends international conferences and as an administrator who seeks to entice talented students from all corners of the world to come to URI, he said he is seeing the damage the restrictions are having. “It is a concern for faculty here that were born in one of those seven countries,” he said. “Even though the law might be clear, how it’s applied may have an impact on our mobility.”

Zawia noted that the effects of the new immigration policies appear to be restricting the flow of students to URI and other US academic institutions. “In graduate education—especially in the STEM disciplines . . . we’re very heavily dependent on international students—it looks like huge drops in applications, a lot of concerns among our students on campus,” he said. “It just sends the wrong message. Graduate education is a strategic asset for the United States. Having the best minds come for an education here, staying, and interacting with our faculty and researchers is the secret to us always maintaining our leadership position.”

On top of the uncertainty surrounding his life as an immigrant researcher and administrator in the U.S., Zawia is grappling with an increasingly unstable situation in his home country, where some of his family still live: 19 million Yemenis are on the brink of a catastrophic famine in a country besieged by civil war. “My personal life and my connections to the country and my family have been upside down, to say the least,” he said.

With all that Zawia has witnessed in the U.S. as a Muslim Arab-American, he views the current political and social climate as the most damaging he’s seen. “I feel the impact of what’s going on now is much greater than what we experienced in the ’90s, with first war in Iraq or 9/11,” he says. “What’s going on right now is really very unsettling and very worrisome. Past events and past wars had more of a selective impact on us as Middle Eastern people and Muslim Americans. But the changes this administration is bringing about in many different facets of life is really . . . disrupting a lot.”

source/content: the-scientist.com / bob grant (headline edited)

____________

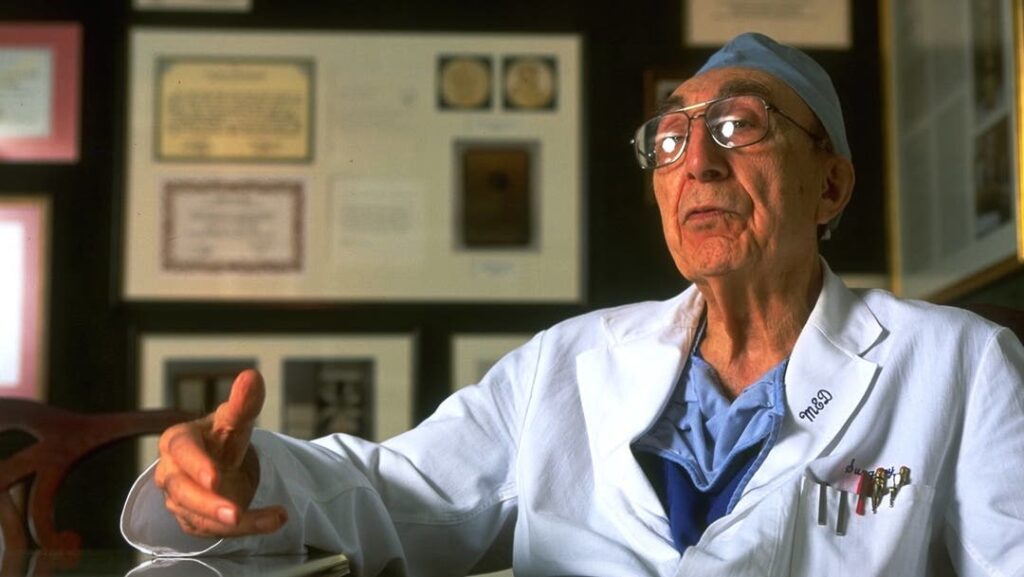

Image courtesy of Nasser Zawia

________________________

AMERICAN / YEMENI